In The World: The mentor helping girls reach their potential

Rachel Scandling, Strategy and Optimisation Lead, left a career in the Royal Navy to join Barclays two years ago

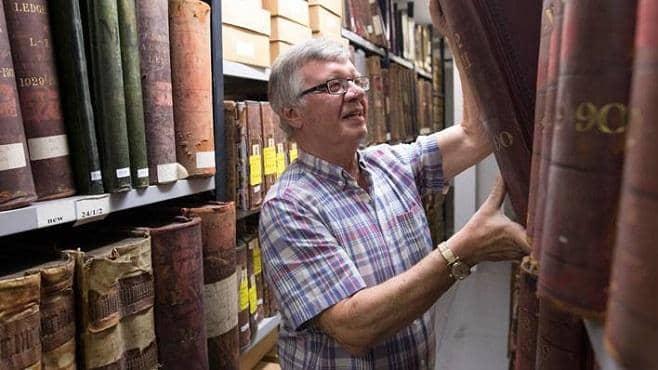

In the second in our series about the impact of Barclays colleagues on wider society, we talk with Alan Thomond, a retired colleague who now volunteers at the Barclays Group Archives in Manchester. He tells us about the satisfaction of delving through 18th century banking ledgers – and the challenges of reading Victorian handwriting.

I had recently retired from my part-time job with a local golf club when I heard from our local retired staff association that the Archive was looking for volunteers. I left Barclays in 2000, having joined Martins Bank in Manchester [a Barclays forerunner] in 1967 and worked my way up to Benefits and Business Case Manager at Radbroke, the bank’s innovation centre in Cheshire. When I joined the bank we were still handwriting a lot of the ledgers – the physical records of customer bank accounts.

I’ve been volunteering for two hours a week for the past three years, along with three other volunteers, also retired Barclays staff. Our job is to index hundreds of 18th and 19th century ledgers from Goslings and Sharpe Bank – one of the banks that merged to form Barclays in 1896. We remove these huge binders from the climate-controlled vault where they’re stored and work our way through them, making notes of account names and dates. Each ledger is slightly bigger than A3 and has about 600 folios, or double pages.

Sometimes the handwriting can be a challenge. Having done a bit of family tree research online I am quite used to reading old ‘copper plate’ handwriting, but it can be difficult when 'ss' looks like 'fs', and capital ‘S’ often reassembles ‘T’. New accounts, while being in the correct alphabetical ledger, are seldom in the correct alphabetical order within the ledger because clerks had to find space in the already bound books. Many new accounts tend to be at the back end of a ledger, where the most room was left.

Volunteering at the archive gets me out of the house and gives me the chance to mix with different people. It keeps me in touch. I was never particularly fond of history at school. Beyond family birthdays and wedding anniversaries, I’m not that good at remembering dates. It was only 10 years ago when I started getting into family research that I became more interested in people’s lives and the impact they’d had on their surroundings. Now, although our role is limited to the name of the account and the end date in any ledger, I take notes of people with unusual names to see if I can find out more.

A while back we were looking into William Pole-Tylney-Long-Wellesley, who was the nephew of the 1st Duke of Wellington, and by all accounts a “bit of a lad”, to put it politely. Doing my own research, I found a group called The Friends of Wanstead Parklands, which was where William’s home, Wanstead House, once stood, before he let it go to ruin. We’ve now shared with them copies of the ledgers, which hopefully will reveal information about how he squandered the family finances. I found out he adopted several names in order to keep his inheritance. Apparently he even travelled to Europe at one point to get away from his creditors!

Volunteering on this project does give you a sense of satisfaction. Having worked our way through 100 ledgers between just the four of us is quite an achievement, though I personally get even more satisfaction when I can find people who are unaware of these old records and are able to make use of the information contained in them. There are about ten groups that are in touch with the archive for various reasons. We can help show where money disappeared to and where it came from.

A good chunk of my job when I worked for Barclays was about getting the best out of staff without overstaffing. It was about processes and time management. They don’t have that sort of work measurement at the archive: it’s not about targets or goals. That’s good, because it means the bank is doing something that it’s not looking for a specific return on. I’ve been impressed that Barclays has undertaken that responsibility. The chance of me seeing this project through to the end is probably a bit slim but I’ve no intention of retiring again just yet.

Rachel Scandling, Strategy and Optimisation Lead, left a career in the Royal Navy to join Barclays two years ago

Keita Era, an Analyst based in Tokyo, tells us about his volunteer work with those badly affected by the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011 – and the fulfilment he gets from supporting them back into meaningful jobs

Tracy Cox-Smyth works as an Executive Assistant in the Investment Bank at Barclays – and volunteers as a “buddy” at sporting events for disabled athletes, including wounded ex-servicemen and women, around the world

Digital Eagle Shweta Walia explains why she joined a programme to train 2,100 Marie Curie nurses to use computer tablets, freeing them to spend more time caring for patients with a terminal illness