history

From the archives: Barclays after World War One

One hundred years ago this Sunday, the First World War came to an end with the signing of the Armistice in the forests of northern France. We look back on how Barclays coped with the demobilisation of thousands of men from the battle lines – and what their return to work meant for the women who had covered “their” roles.

“We have emerged from the greatest upheaval of humanity that the world has ever witnessed. We have now before us the brightest and most encouraging possibilities that were ever open to any section of the human race.”

This was how Barclays Chairman Frederick Goodenough described the now unimaginable situation facing Britain after the First World War, as thousands of men from around the world began to be reintegrated back into ordinary life after four years of conflict.

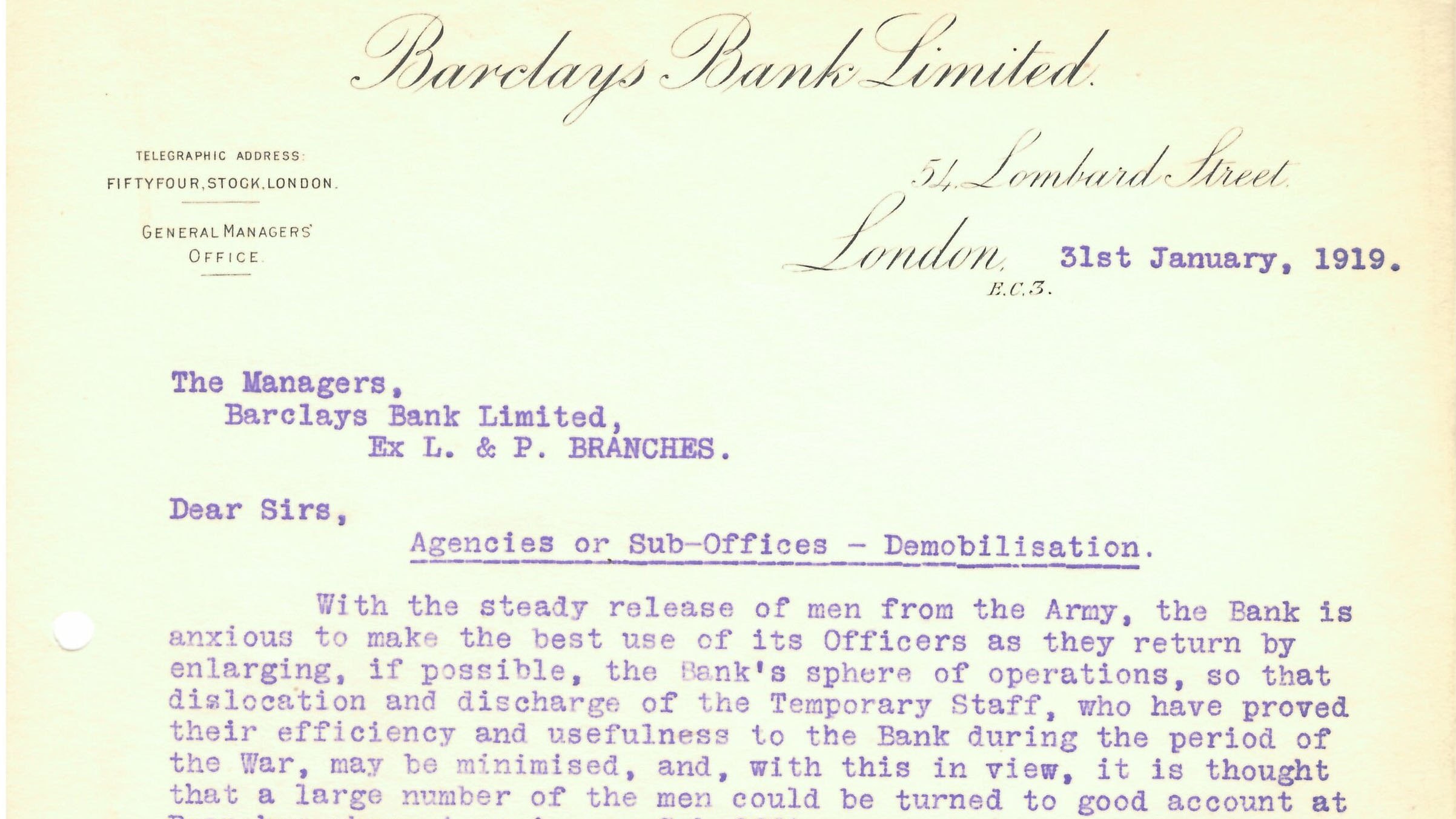

For the bank, like the country, this was a period of upheaval. Over 4,300 men from Barclays and associated banks had been in service, with 645 losing their lives. The demobilisation of surviving servicemen meant that the number of permanent male staff at the bank more than doubled between 1918 and 1919. From a purely administrative point of view, the process of reintegration was laborious, with files showing that the bank had to fill in forms for every recruit before they could be released from the Army.

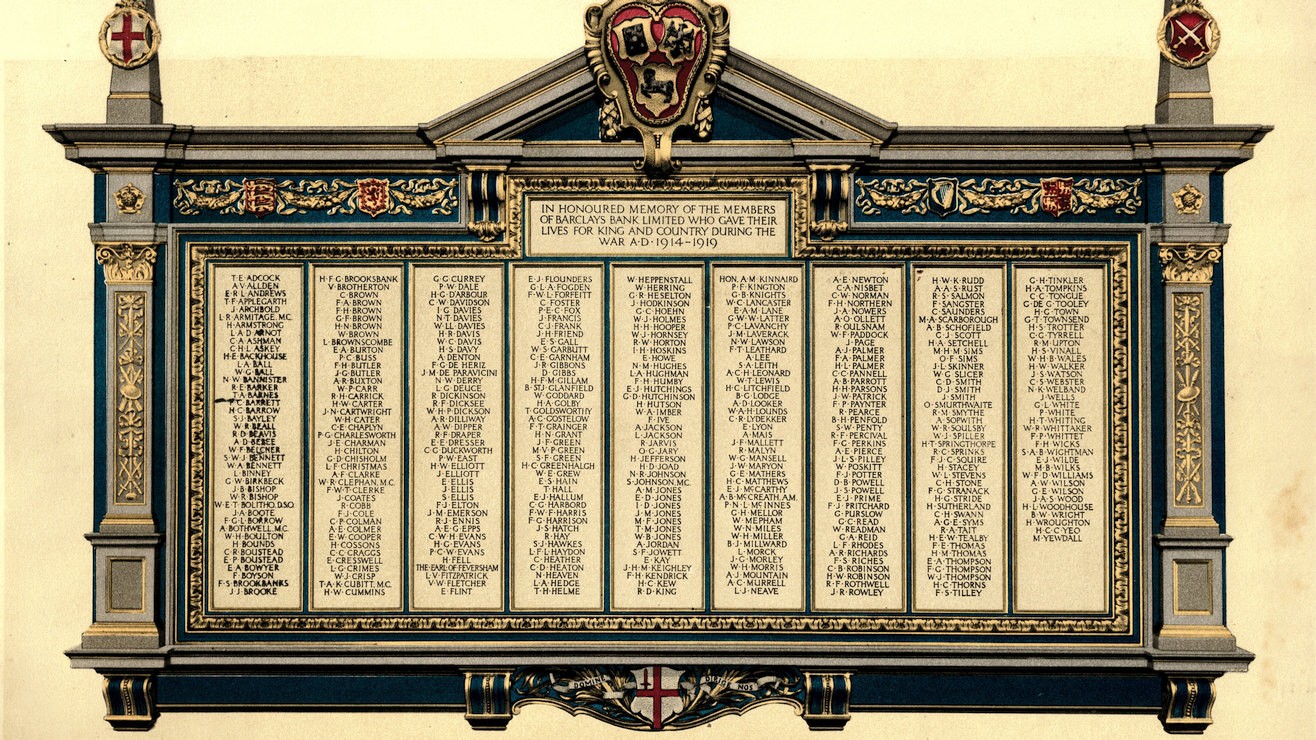

War memorial with the names of Barclays colleagues who lost their lives in WWI

Branches, sub-branches and agencies were reopened to pre-war levels, as Barclays – recognising the importance of getting the economy, trade and business back on its feet – formed an intelligence department, gathering information on foreign economies and business practices to supply to corporate customers.

The end of the war also saw the establishment of a Swiss department and the expansion of Barclays’ European subsidiary, Cox & Co, which had been set up to provide services to the British Army during the war and had offices across France. Barclays also played an important role for ex-military customers, with head office circulars detailing the complications of cashing demobilised soldiers’ postal drafts.

Many of the 4,000 temporary female staff that worked for the bank through the war had to leave their roles to make way for returning soldiers. The number of men on the bank’s rolls of permanent employees rose from 2,816 to 5,673 between 1918 and 1919, with the equivalent permanent female workforce moving from just 20 to 26. By 1920, there were 6,802 men and 38 women permanently employed by the bank.

Temporary female staff at Barclays' Broad Street office

Like any business, Barclays suffered terrible human losses from 1914 to 1918. Of the six million British men who were mobilised, over 700,000 were killed. The bank kept leather-bound rolls of honour, and a plaque was created and mounted in the banking hall of Barclays’ Lombard Street base in London. The rolls, also encompassing the Second World War, are now kept alongside a plaque at the bank’s London headquarters.

War hero: Reginald Billingham

Reginald “Rex” Billingham joined Barclays in 1911, aged 23, but by May 1917 he was stranded in a shell-hole, separated from his unit and surviving four nights of mortar and grenade fire from German troops in the French countryside.

Corporal Billingham from the 2nd Battalion Honourable Artillery Company were attempting to take the ruined village of Bullecourt, in Picardy, crossing a wasteland strewn with the bodies of a British division that had launched an identical attack the previous day. His battalion lost over 200 men in the attack, leaving Billingham and his party of nine men stranded and suffering constant enemy fire.

Billingham wrote: “On the second night, a party of three or four of the enemy appeared within a few yards and we challenged them. Their surprise was almost comic. They halted dead and stood motionless until, perhaps seeing the glint of steel in the moonlight, they turned and fled screaming back to their own trench. We fully expected to see the Germans send out a mopping-up party and wipe us out, but they contented themselves with the firing of rifle grenades and a few trench mortar bombs.”

By the third day, Billingham – who was now suffering a shrapnel wound – and his men resolved to risk crossing enemy lines in a bid for safety. “This was pretty hopeless,” he wrote, “but better than dying like rats in a hole.”

Military historian Paul Kendall, who uncovered Billingham’s story in an Honourable Artillery Company journal, said: “Billingham heroically advanced under a hailstorm of machine guns, against all odds into the ruins of Bullecourt.”

He was awarded the military medal by General Gough, who Kendall said had presided over “an important lesson in how not to conduct a battle”. Approximately 10,000 Australian and 7,000 British soldiers lost their lives during the capture of Bullecourt.

Billingham was promoted to Sergeant and fought on the Italian Front until the end of the war. Returning to Barclays, Billingham rarely spoke about his wartime experiences, becoming a bank manager in St. Albans and seeing out his career as Principal of the Stamping Department. He retired at the age of 60, in 1948, and his family remained unaware of the trauma of Bullecourt until a wartime journal was discovered after Billingham’s death, in 1965, at the age of 77.

Clerks in Barclays' Lombard Street head office, where Reginald Billingham worked after the war

A head office circular from 1919 detailing issues around demobilisation