History

From the archives: blinded by war, employed by Barclays

After World War Two, Barclays played a pioneering role offering jobs to hundreds of ex-servicemen who had lost their sight during combat. Drawing on archive documents and photography, we tell the stories of the blind men employed as telephonists at a time when there was little employment for people with disabilities.

“After almost five years of army life in wartime, I was very keen to try this opportunity of regular work and settle down with my small family.”

Alf Bradley was one of thousands of servicemen who lost their sight during combat in World War One and Two, and returned home to face little prospect of support or employment.

Many of them, including Bradley, went on to join St Dunstan’s – today known as Blind Veterans UK – a British rehabilitation charity for blind ex-servicemen and women established in 1915. The founder, Sir Arthur Pearson, aimed to help blind people find independence and employment through basic training in braille and typewriting, as well as vocational training like bootmaking, poultry farming and telephony.

Materials from the archives reveal that Barclays was one of the first to recruit newly trained blind telephonists from St Dunstan’s – despite them having no banking experience – in a pilot scheme launched in 1946. Initially taking on three new recruits, that number grew to over 150 by the 1970s.

The pioneering move reflected Barclays’ commitment to the Disabled Persons Employment Act, a historic piece of legislation enacted only two years previously, which was the first of its kind. Designed to support disabled people, it ushered in the introduction of employment quotas for businesses.

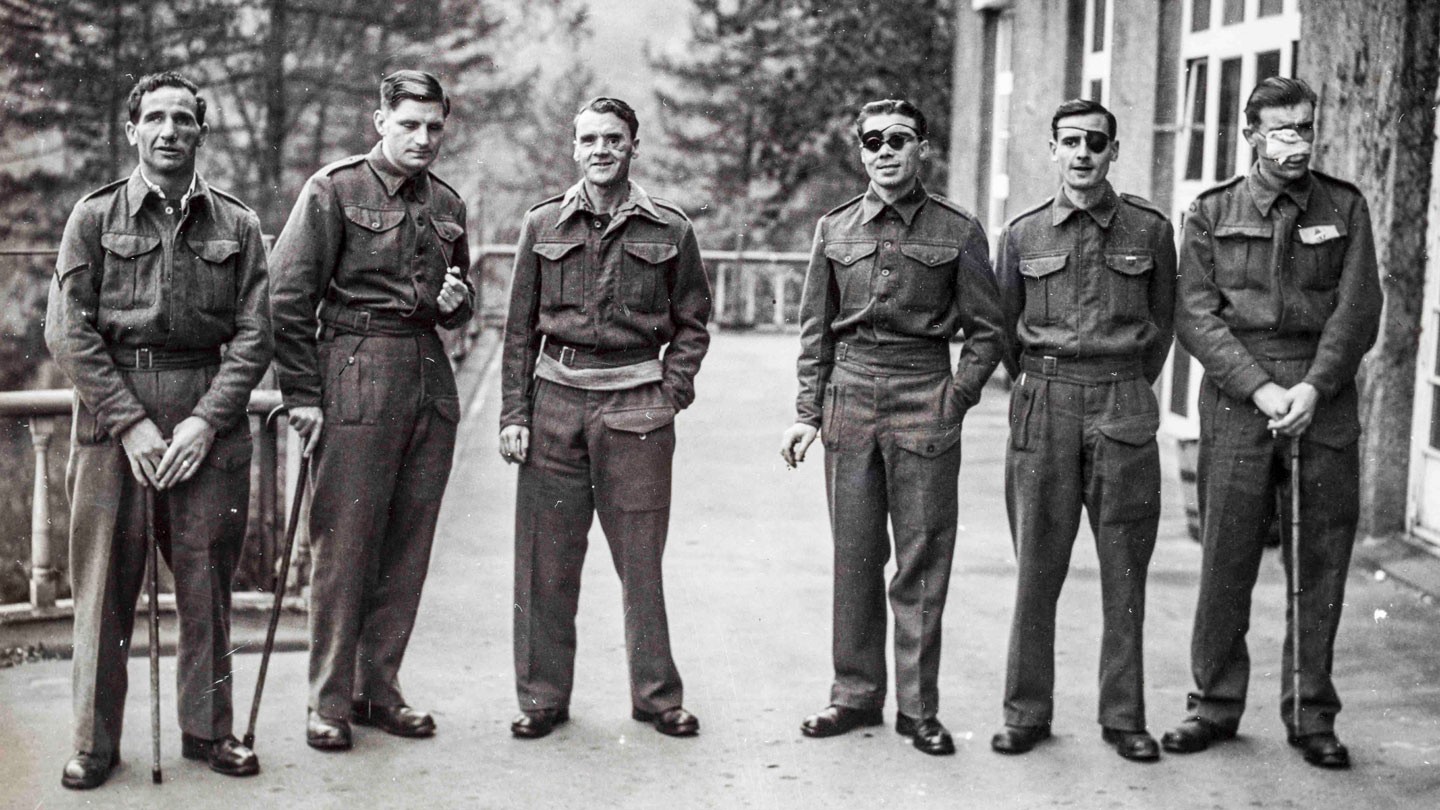

Dennis Fleisig (centre) at St Dunstan’s training and rehabilitation centre in Church Stretton, Shropshire.

The first blind telephonist

Alf Bradley was the first blind telephonist to join a bank in the UK. He started at Barclays in 1946 after completing his training at St Dunstan’s, and went on to stay with the bank for over 30 years. In a letter to the bank’s staff magazine in 1990, he looked back at his experience of readjusting to civilian life – and his new role as a blind telephonist at the Piccadilly branch in bustling Regent Street, London.

He explained how, for the first few weeks, his wife had to accompany him to work “to help me cope with the locality… until I got the whole of travelling pretty well in hand”. Soon at ease, it was then just “a matter of finding subway number one”.

This was only the start of Barclays’ commitment to inclusivity. Bradley related how “a steady stream of St Dunstaners followed me in the years to come”, saying that by the time he retired in the late 1970s, “visually handicapped telephonists were in branches over much of the UK”.

The Barclays Bank Blind Telephonists Cricket Club

Rob Baker, Information and Archives Executive at Blind Veterans UK, told us that Barclays “was a significant employer” for ex-servicemen – and changes within the bank reflected that. In 1963, for example, Barclays produced an edition of the Staff Handbook in braille, becoming the first bank to think of doing so for its staff.

“The bank was specifically mentioned in the autobiography of our former Chairman Lord Fraser as one of the ‘big firms’ who ‘kept asking for more’ of our telephonists!” said Baker. “This is testimony not only to the ability of our telephone operators but to the positive-minded approach of Barclays, which was the first bank to employ a blind telephonist, our veteran Alf Bradley.”

More widely, he explained, “Barclays helped shift societal opinions about the capabilities of the blind, by showing how, given appropriate training and support, they can and should work alongside the sighted.”

In 1970, the Barclays Bank Blind Telephonists Cricket Club was formed and had no shortage of possible players – there were by this point more than 150 blind telephonists working in London branches alone.

A document from the archives explained how “the game was played with as strict an adherence to the rules as possible” – using a large plastic ball filled with lead that, when bowled, created a “swishing noise and bounced with a pitter patter sound”.

After a rocky start to their first season, the team went onto play seven matches – “two won, three drawn and two lost” – in their second.

Bill Cowing swapped factory work for telephony in 1950 and gained employment at Barclays, where he stayed until his retirement.

From blind telephonist to MBE

The blind telephonists at Barclays were not all ex-servicemen. Keith Hancox was 18 when he lost his sight in a motorcycle accident in the early 1960s. He retrained as a telephonist at the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) and later gained employment at a Barclays branch in Birmingham in 1967. He was the first blind telephonist in the area and soon made a name for himself.

Hancox remembered up to 2,000 telephone numbers by heart, and was praised for delivering a personal service – he could recognise customers by their voices, or even by their coughs. Following a successful career at the bank spanning over thirty years, he was awarded an MBE for his services to the blind in banking. In an RNIB magazine article, Hancox looked back fondly on his time as a blind telephonist at Barclays, remembering the “camaraderie” of his team. He added: “In 37 years, there was never a Monday morning where I thought ‘Oh no, it’s work today’.”