History

From the archives: October’s freedom from slavery

In the late 18th century, Barclays partner and avowed abolitionist David Barclay set about resettling enslaved men, women and children in Jamaica as emancipated people in Pennsylvania. We learn the story of one free man and his descendants.

October Barclay arrived in Philadelphia in 1795, aged eight, was placed with a craftsman to learn how to read and write, and apprenticed as a chair maker. Growing up to marry and father four children, October died aged 73 in 1861, after a career as a cabinet maker and painter. The Eden Cemetery in the western suburbs of Philadelphia – the oldest existing African-American cemetery in the US – is the final resting place of October Robert Barclay, who had been born into slavery in Jamaica.

October’s life in America, and those of his many descendants, began with a connection to two Quaker abolitionist partners of Barclays.

In the 18th century, Unity Valley Pen was a grazing ground worked by enslaved people in the interior of Jamaica, then a British colony. As a result of a collateral on a debt, the land and its inhabitants fell into the hands of London’s Barclay brothers, John and David – early partners in Barclays Bank.

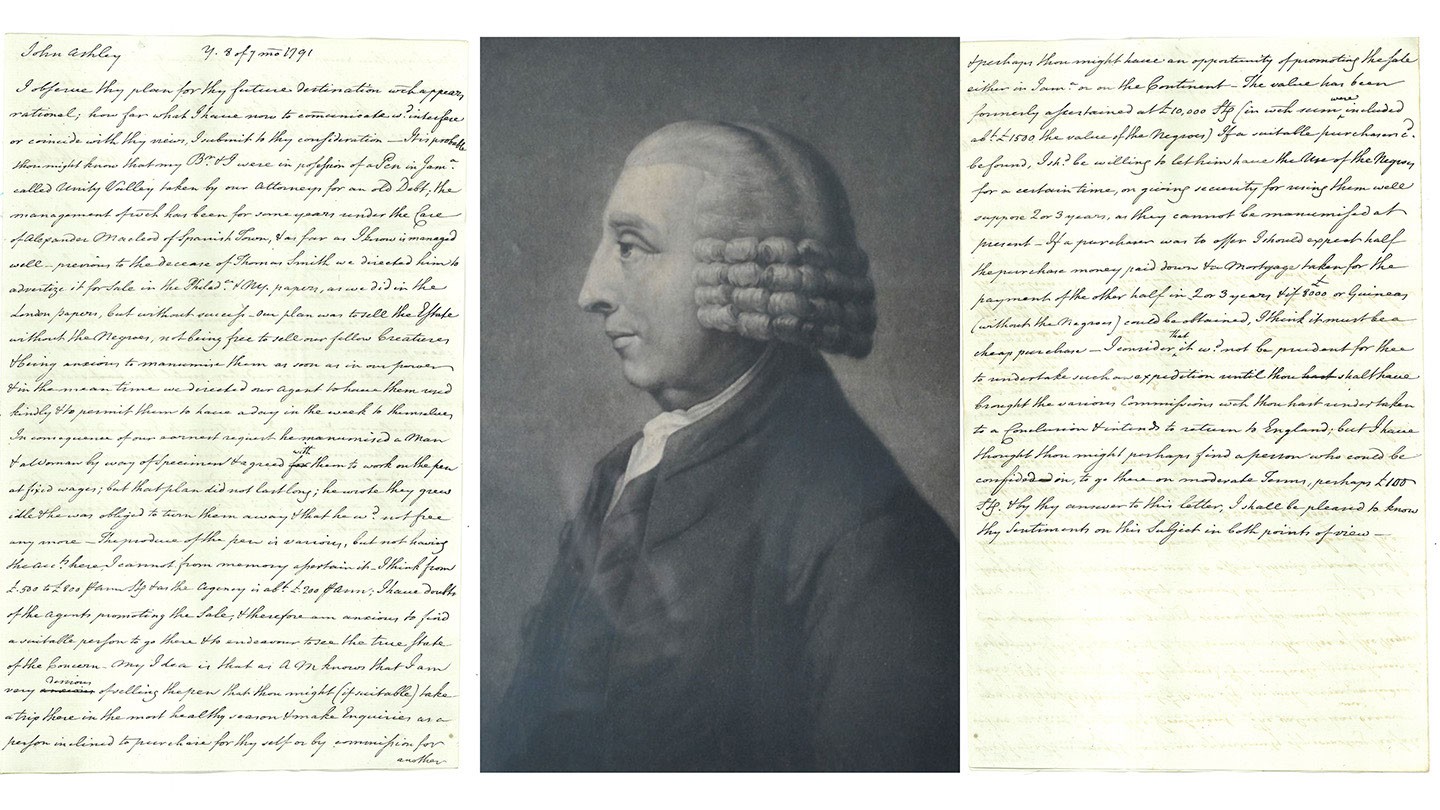

A letter written by David Barclay in which he expresses his wish to free the enslaved people.

As a prominent Quaker family, the Barclays, at odds with much of the City of London at the time, found slavery abhorrent. In support of William Wilberforce, they campaigned for the abolition of what David called “that horrid traffick, the slave trade”. However, family records, confirmed by University College London’s Legacies of British Slave-ownership Project, indicate that they had been mortgage holders of a plantation in Barbados, a debt which they passed on after five years.

On acquiring Unity Valley Pen in St Ann, Jamaica, sometime around 1785, the brothers determined to emancipate the enslaved people held there. After John’s death, the project accelerated, with David Barclay writing: “…the retaining of my fellow creatures in bondage was not only irreconcilable with the precepts of Christianity, but subversive of the rights of human nature”.

Philadelphia freedom

David Barclay freed two of the enslaved people in Jamaica, before concluding that life was too arduous even for emancipated workers on the island. The Barclay family had connections to the Quaker settlers of Pennsylvania. At the time, Philadelphia had one of the largest Quaker and emancipated African heritage communities in America. Through his friendship with the American thinker and politician Benjamin Franklin, David was aware of this, as well as of a society in the city dedicated to “improving the condition of free blacks”.

Two of those who remained on the plantation were considered too unwell to travel, but plans were put in place to free the remaining 30 men, women and children and transport them to the American city. The expense of the operation – sending agents to Jamaica, hiring a ship, establishing members of the new community in trades – amounted to a large sum for the time.

“No man,” an obituary of David Barclay later stated, “was ever more active than David Barclay in promoting whatever might meliorate the condition of man. Largely endowed by providence with the means, he felt it to be his duty to set great examples.”

Just maybe their story has the power to heal and promote reconciliation

October Barclay’s great-great-grandson and Historian of the African Diaspora

David Barclay, abolitionist partner of Barclays, funded the emancipation of 30 enslaved people in Jamaica.

The 30 passengers – 12 of them children aged between four and 14 – took the surname Barclay and made the six-week journey to Philadelphia where, like October, they were apprenticed as ‘free blacks’. Two emancipated men – the Reverends Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, who founded the Free African Society, set up to support widows, orphans, the sick and the unemployed in the community – were crucial in taking in and providing support to the passengers once they arrived.

Six years later, David revisited his experiences in a pamphlet, giving an account of Unity Valley Pen and arguing strongly in support of the British abolitionist William Wilberforce.

Relocation and opportunity

Reports in 1796 indicated several of the freed 30 people were comfortably settled in Philadelphia, and those who could not support themselves benefitted from funds given to the Committee of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society by David Barclay through his agent.

October, who was renamed Robert, went on to marry Elizabeth Depee, a free woman of Haitian descent. The family was active within the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia, continuing to work for the freedom of enslaved African heritage people. Robert Barclay became a lifelong member of the African Episcopal Church of St Thomas, the church founded by the Reverend Jones, who was also the first African American to be ordained in the Episcopal Church in the US.

Robert’s immediate descendants included barbers and accountants, and later American soldiers in both World Wars. Some of his great-grandchildren – the oldest of whom, George Forrester Barclay (fourth from the left) is said to bear the strongest resemblance to Robert – are pictured above.

A branch of the family relocated to Newport, Rhode Island, where Robert’s great-great-grandson Keith Stokes is a Historian of the African Diaspora. He writes that “my life and interest in African heritage and history has been shaped largely by the words of my Barclay grandmother who would remind me as a boy that, ‘Slavery is how we got here, but it tells you little of who we are as a people’”.

Keith Stokes and Humphrey Barclay, descendants of October and David.

In the course of researching his ancestor's story, Stokes connected with a descendant of David and John’s half-brother, Alexander – Humphrey Barclay, the current Chief of the House of Barclay of Mathers and Ury, who, as a television executive, produced the British-Caribbean sitcom Desmond's, which was broadcast on the UK’s Channel 4 in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

In letters between the two men, Stokes addressed the complex issue of 'slave names', saying: “Our Barclay name has never been seen as anything less than a proud mark of the ‘creative survival’ experience of the African heritage family. Our generations of success is due to the benevolence and opportunity your ancestor David Barclay provided for a little Jamaican boy over 200 years ago, along with the support of African heritage religious and civic organisations.

“Young October and his historical link to David Barclay can and should speak to the humanity of both men – young and old, black and white – who sought to make their world a more just place. Just maybe their story has the power to heal and promote justice and reconciliation.”