Innovation

Helping Black America achieve financial parity

19 May 2021

With US $5m in seed funding from investors including the Female Innovators Lab Fund, neobank First Boulevard aims to provide innovative banking services for Black communities in the US. Co-Founders Donald Hawkins and Asya Bradley tell us why the murder of George Floyd was a tipping point – and how their business can help address systemic racism and “help Black America reach some level of financial parity”.

“In the United States, we've become accustomed to tragedies,” says Donald Hawkins, Founder and CEO of First Boulevard. But, he says, after the publicly recorded murder of George Floyd, coinciding as it did with the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of colour, there was a widespread feeling that people “couldn’t go back to regular life”.

“You couldn’t go back to brunch,” he continues. “People were asking themselves, ‘Why does this continue to happen?’, and we were having some of the toughest conversations that American households had ever had.”

The murder of George Floyd has prompted “some of the toughest conversations that American households had ever had,” says Donald Hawkins.

It was in this new climate that Hawkins, a serial entrepreneur with years of experience in technology and financial services, together with serial founder Asya Bradley, decided to create First Boulevard.

“We know that financial control is an important way of fighting back against racism and that, when it comes to financial services for the Black community, a centralising force is long overdue, so we both agreed that a financial platform could be used to help Black America out of its oppression,” he says.

Empowering Black America to take back financial control

First Boulevard describes itself as a neobank that aims to empower Black Americans to take control of their finances, build wealth and reinvest in the Black economy with sophisticated, digitally native financial instruments built for the 21st century.

The bank’s digital platform, due to launch later in 2021, already has 200,000 customers on its waiting list. Hawkins and Bradley have identified four “stages” of customers who can benefit from their products: debtor, saver, investor and legacy builder.

With its latest raise, First Boulevard aims to expand its mission-driven team, increase its customer base and grow the platform to offer fee-free debit cards, financial education, technology to help members automate their saving and wealth-building goals, and ‘Cash Back for Buying Black’, a Black business marketplace which offers up to 15% back when members spend money at Black-owned businesses.

“Saving is something that we haven’t been taught as a community”, says Hawkins, and the bank’s loyalty points and budgeting insights are designed “to lead customers to make positive financial decisions”.

Donald Hawkins, Founder and CEO of First Boulevard – a neobank offering innovative banking services for Black communities in the US.

What we're doing is trying to create another medium for Black America to get financial parity. We represent our community and want to make sure they get the very best that we can offer.

Founder and CEO, First Boulevard

Bradley, who serves as First Boulevard’s COO, says: “The current financial industry was not built to serve the needs of melanated people, because we were excluded from its construction. First Boulevard understands the unique needs of the Black community and is our modern-day approach, using digital banking and wealth-building to help Black America reach financial parity.”

Beyond finance: how Barclays’ networks made the difference

A major part of launching First Boulevard was ensuring the founders had the right investors around the table who would actively support under-represented founders and share in their vision for helping Black America build generational wealth. Recalling the moments before her first encounter with the Female Innovators Lab Fund team, Bradley says: “Barclays and Anthemis weren’t your typical venture capitalists and we needed to make sure that whomever joined us was going to be mission-aligned with what we wanted to build.

“When we met, though, we thought, ‘These are our people, these are the folks that are going to really help build this product.’ And since then, it’s been a very supportive relationship. The Lab team really helped us to see around corners and guided us through the investment process.”

“We’re living our ancestors’ wildest dreams”

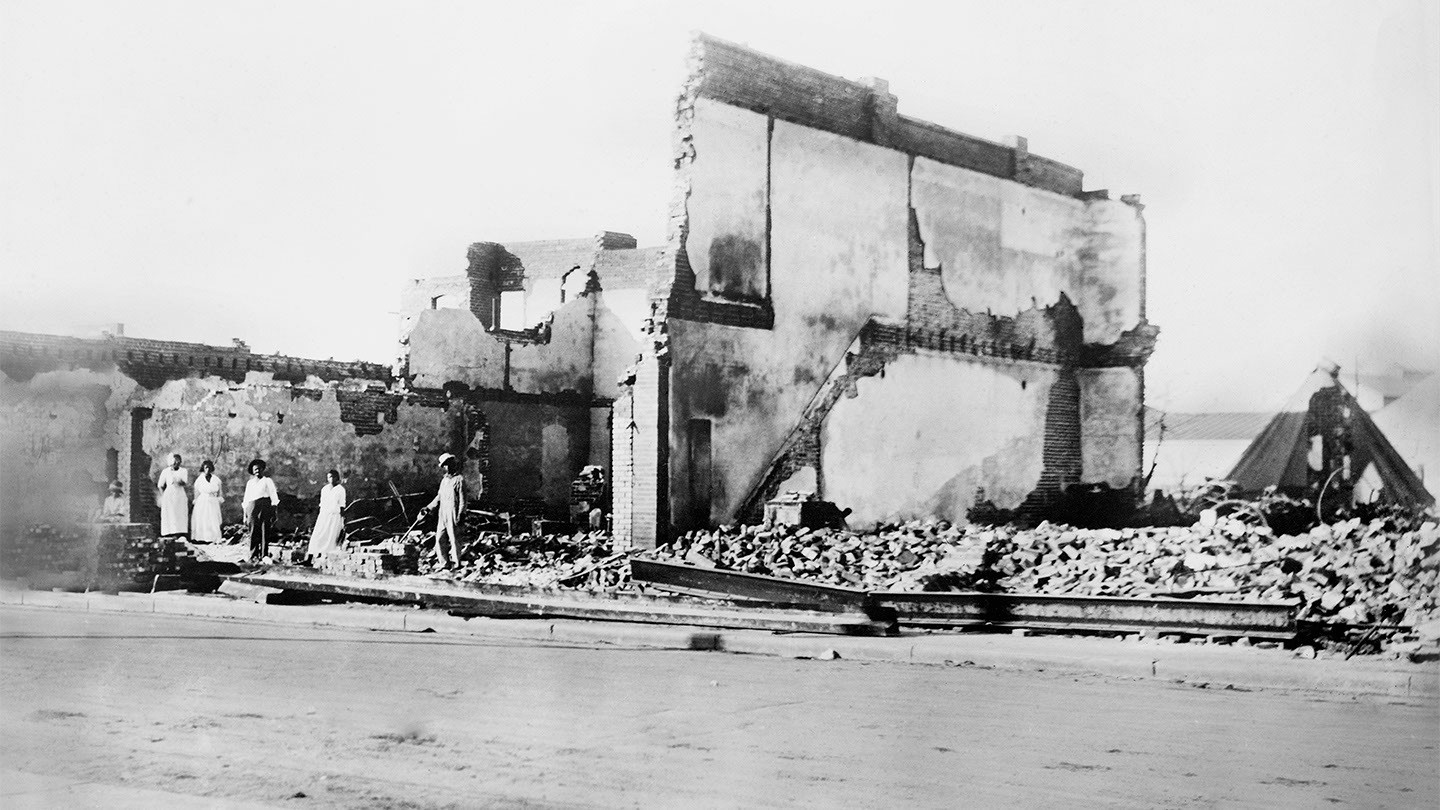

Reflecting on the often violent reactions to the Black community’s attempts at financial self-sufficiency and wealth building, Hawkins says: “We’re living our ancestors’ wildest dreams because we don't have to worry about a brick-and-mortar location being blown off the face of the map like in Black Wall Street in Tulsa, and we don't have to worry about money being taken from us like it was from Freedman's Savings and Trust Company, because we now have the luxury of sitting on this digital banking platform protected by our sponsor bank.”

Black-owned banks have, he says, historically faced institutional problems in serving their customers – and barriers remain. He’s clear that systemic racism in banking services still exists and needs to be addressed.

Black Wall Street in Greenwood, Tulsa, following the Tulsa race massacre in 1921.

Hawkins’ own background has informed his determination to make change. He describes himself as a “country boy”, having grown up in the “small city of Albany in South Georgia”, and counts himself as “fortunate” to have grown up in a middle-class household.

“But my father was the first person to integrate his high school, and my grandmother grew up as a sharecropper. As a result of that, I grew up aware of so many other people that looked like me in my hometown who had a lot of difficulty, even in my extended family. And it never felt right that people struggle the way that they struggled.”

First Boulevard Co-Founder Bradley was born in South Asia, “in a home without water or electricity”. Her family’s emigration to Canada began a globetrotting life covering Amsterdam, Cairo and California. During a varied career, she developed an understanding of how fintech can contribute to social change.

“Then George Floyd happened,” she says. “And I just thought that I can't keep going through the motions while the world is falling apart around me. For me, the sense of urgency was really born from that moment where I felt like I needed to do something to solve this problem.”

“We’re built by the people we’re trying to serve”

Black communities in the US, says Bradley, are “massively underserved, but that doesn’t mean they’re less desirable customers”. She cites the case of Jimmy Kennedy, an NFL footballer denied access to private client status at a major bank, and other cases where “Black people just literally trying to get money out of their account have the teller call the cops on them”. The bank that removes these hurdles could unlock the US $1.4 trillion annual spending power of Black Americans, building wealth and reinvesting in the economy, she believes.

This is our modern-day approach, using digital banking and wealth-building to help Black America reach some level of financial parity.

Founder and COO, First Boulevard

Asya Bradley, Founder and COO of First Boulevard.

Bradley is also proud that First Boulevard “walks the walk” on hiring, with 85% of the neobank’s team of 24 currently made up of Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) and a 100% BIPOC leadership team. She says: “If you open your eyes and look at the person and the talent, it’s not difficult to have a diverse workforce.”

The pair are clear that First Boulevard is not intended to be exclusively for one community. “We’re open and inclusive,” says Bradley “but the differentiator is we’re built by the people we’re trying to serve.”

Hawkins adds: “Right now, the banking system doesn’t really have the lens of oppressed communities, and that lack of diversity shows itself in a variety of ways. What happened to Jimmy Kennedy wasn't one bad manager and one employee. For the industry to truly fix itself, it's going to have to look like the world and the audience that it wants to serve.

“What we're doing is trying to create another medium for Black America to get financial parity. We represent our community and want to make sure they get the very best that we can offer.”