From the archives: Recruitment then and now

The drive for Barclays to identify top talent began more than 325 years ago

Maria Sienkiewicz, Barclays’ Group Archivist, takes us through the workings of Barclays’ Archives and looks at some of the more interesting artefacts stored deep within the vaults.

Tell us about your career path to Barclays?

I decided I wanted to be an archivist when I was 14, which is quite unusual! I’ve loved history for as long as I can remember, and did a history degree, but you don’t need to have a history degree to become an archivist.

Managing archives requires good research, analytical, organisational, and communication skills, so any degree which allows you to develop those is perfect.

After my degree, I applied for a place on a one-year postgraduate archive training course. Once I’d qualified, I worked in the public sector for eight years, where the majority of archivists work, and 12 years ago, the archivist who’d given me my first trainee job at Barclays retired and suggested I apply for her job. With her encouragement I applied, and got the job.

What types of artefacts do you store at the archives?

The Barclays Archive exists to preserve and provide access to records which are being retained permanently for legal, business or historic reasons. Some of these we have to keep by law – things like the Board minutes, for example. Other records we choose to keep because we think they will be useful to the business, or because they will be historically significant in the future, particularly in telling us something about the organisation’s history and evolution.

What special conditions do we store our items in?

The archives are stored on approximately a mile and a half of shelving in purpose-built strongrooms. They maintain a constant temperature and humidity, optimal for the preservation of paper. They are fitted with super-sensitive fire detectors, and an inert gas fire suppression system, which extinguishes a fire by starving it of oxygen. Water sprinklers are a big no-no in archives as a faulty sprinkler can cause almost as much damage as a fire.

Each item in the archive is logged on a database with a unique identifier and location reference, but we are a very long way from having a digital image of everything, and still do most of our work with the hard copy originals.

Our website, www.archive.barclays.com contains thousands of digital images taken from our collection, yet we estimate this to only be about 1% of the total.

How do Barclays colleagues use the archives?

We work closely with colleagues in managing the statutory records of the bank and its many subsidiaries.

We also work with Barclays colleagues across a range of departments around the world, from colleagues in our legal function, who use the records to support their investigations and reviews; the customer relations team who use information about our various products to assess customer complaints, to colleagues in corporate relations who use the archives to promote the brand and raise awareness of our long history – whatever the request, we always try our best to help.

Describe a typical day for you

One of the things I love about my job is that every day is different. More often than not, we’re kept busy dealing with enquiries from colleagues and members of the public. Anyone is welcome to contact us, and while we have strict rules about what we can share with the public the vast majority of our records are accessible. When we’re not busy with enquiries, it’s great to spend time sorting through new arrivals to the Archives – everything needs to be appraised to determine if we want to keep it, then catalogued onto our database, and packaged before being safely stored away in the storeroom.

We need to make sure we’re capturing things now that will be needed in the future. The current programme of structural reform is the biggest organisational change in Barclays’ history, so it’s incredibly important that we ensure we’ve got everything we need to accurately record what is taking place. The last time Barclays did anything approaching this scale was in 1985 when the international and domestic banks merged, and we get asked about that on a regular basis.

It’s also important that we continue to collect more ‘everyday’ records – current policies, procedures, advertising, premises records, project papers, committee minutes.

Digital preservation is a big concern for us – the majority of the bank’s records are now created electronically, so that is how we should be storing them. A fair chunk of my time is currently spent with IT, discussing the best way of ensuring that anything we store will be secure and still accessible in 20, 50, even 100 years’ time.

I also get to publicise the archives and tell stories from our past – we regularly contribute articles to in-house and professional archive publications, and requests for us to speak about our work come from across the bank and the wider archive sector.

Of course, I don’t, and couldn’t, do all of this on my own – we are a team of four here in the Archives, and I absolutely couldn’t manage without my colleagues.

The Barclays Archive is a treasure chest. Maria takes us through some of her favourite items and artefacts stored at the archives

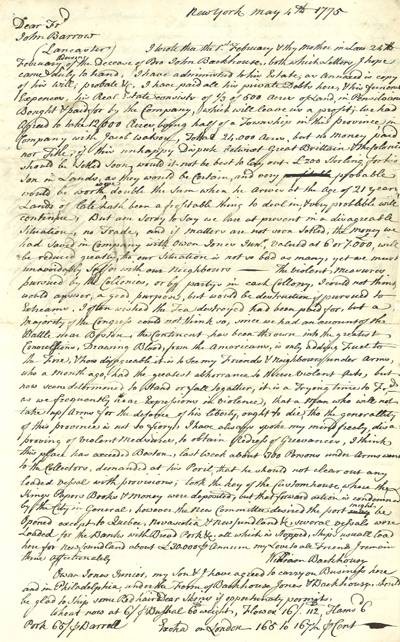

This is a letter written by William Backhouse from New York in 1775. The Backhouse family founded a bank in Darlington which went on to become part of Barclays. Like many of our early founders, the Backhouses were Quakers, and had links with Quakers who’d settled in America. The letter is written during the time of the American War of Independence and makes reference to the Boston Tea Party. Backhouse describes the anguish he feels in seeing fellow Quakers taking up arms. What makes this letter special is knowing that it was written by someone witnessing one of the most important events in world history – reading Backhouse’s very personal reflections on these tumultuous events makes them really come to life.

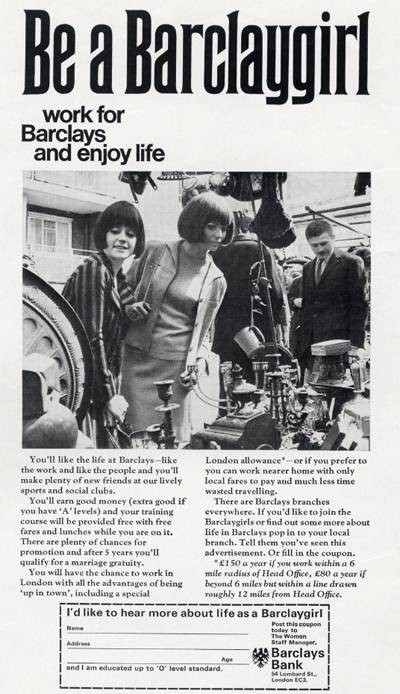

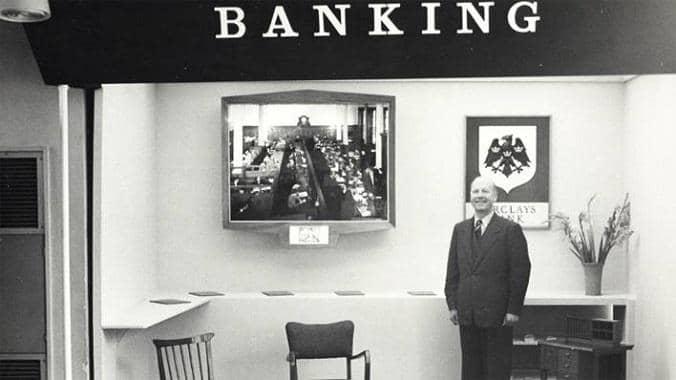

This is a recruitment advert from 1967, and I love that it is so completely 1960s. Bank advertising really took off in the 1960s – up until then, banking had been terribly restrained and the banks wouldn’t have dreamt of competing openly for customers or staff. However, the 1960s was a time of huge social change – women were actively recruited for the first time, and although this advert may seem rather patronising to modern eyes, at the time it represented a big step forward for the banking world.

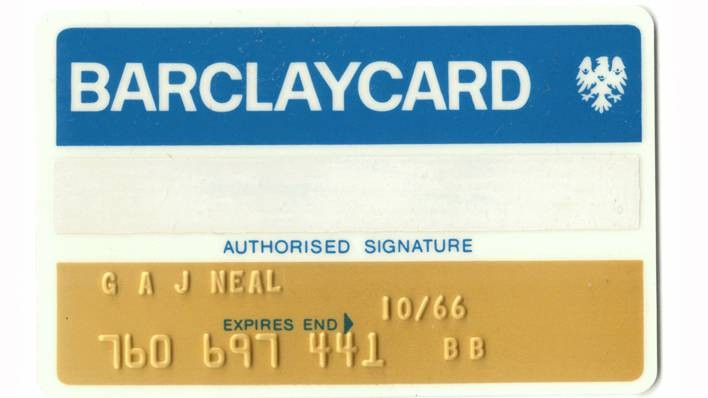

Our original 1966 Barclaycard always makes me smile. It is a small piece of plastic, but it represents a huge development in our history. Not only was it the UK’s first credit card, it was conceived and launched in just six months, and ushered in a whole new approach to advertising and branding. It symbolises Barclays’ pioneering can-do attitude like nothing else in our collection.

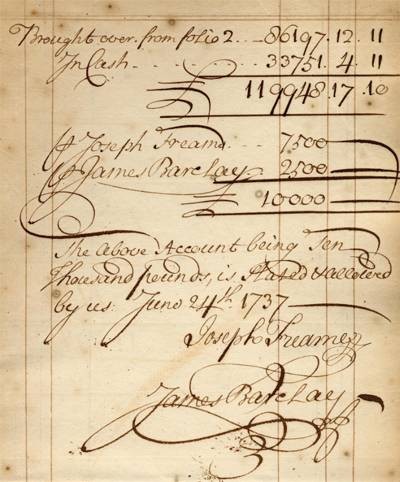

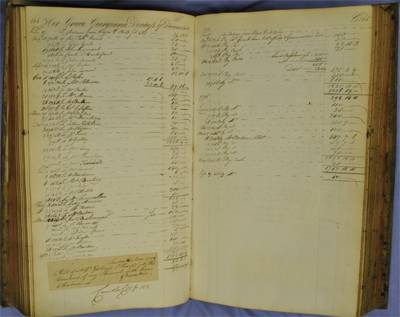

Barclays traces its history back to two goldsmith bankers, Freame and Gould, who set up their business in 1690. In 1736, Freame’s son-in-law James Barclay joined the partnership – the first Barclay in the bank. This is the last page from their annual balance, which comprised a list of all their customers, followed by a calculation of their profits, which was signed by both partners. This record reminds me that the Barclay name does not just belong to a huge corporation, it belongs to a human being.

I also love the fact that this document is clearly a predecessor of our modern annual report, and that is a theme you can find throughout our records – while technology has obviously changed the way in which we do business, many of our basic processes remain the same, and echoes of our past can be found everywhere.

These are the customer ledgers for the bank of Goslings and Sharpe of Fleet Street, which became part of Barclays in 1896. There are 658 ledgers in total, and each one is slightly different because their bindings are hand-stitched. Although we do not collect modern customer records, we have decided to preserve these because it is incredibly rare to find such a complete set of customer ledgers, and we can learn so much from them about the early days, and the development of banking.

We can also learn a huge amount about the people whose accounts are contained within the ledgers, and they have been used to great effect by a variety of researchers. The National Trust, for example, has used the account of the Earl of Bristol to track payments relating to his house, which they now own. By tracking payments they have been able to accurately date work on the gardens, and the painting of a portrait.

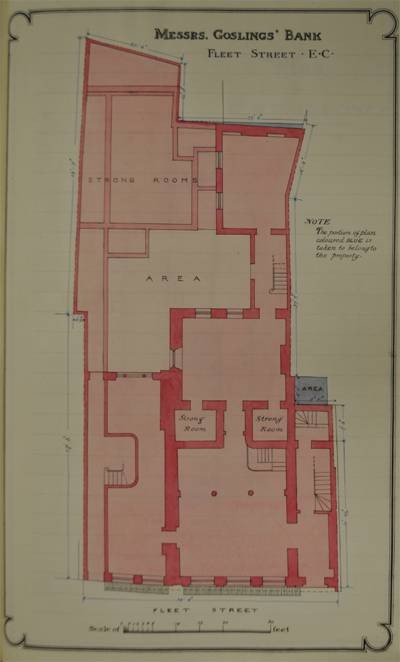

Barclay and Company Limited was formed in 1896 through an amalgamation of 20 small private banks. One of the first things the new company did was commission a survey of all the premises it had inherited from its constituents. The surveys were recorded in five leather-bound, gold-tooled volumes, and each survey comprised a very detailed description of the premises, together with a simple floor plan. Some 168 buildings were covered in total, and the surveyors considered the state of repair of the premises, and their potential. These volumes provide a beautiful snapshot of a bank as it moved from old family traditions to modern organisational procedures, demonstrating how buildings reflect, respond to and influence working practices, social status and corporate ambition.

The drive for Barclays to identify top talent began more than 325 years ago

Smartphone-based cheque imaging is just the latest development in the long history of the cheque

From the moment the velvet curtain was drawn back at a Barclays branch in London’s Enfield, the way we bank was altered forever

“Bank manager is a WOMAN” shouted the headline of the Daily Mirror, on 17 May 1958